Interview With Animation Story Artist David Trumble

Interview With Blitheness Story Artist David Trumble

InterviewsAnimationstoryboarding Disclosure: This mail may contain chapter links. That means if you buy something we get a small commission at no extra toll to you(learn more)

In that location are dozens of paths to follow when information technology comes to entertainment art. But story art might be the most varied (and possibly the virtually complex).

Information technology feels like a mix betwixt writing, character design, and directing all rolled into ane. It'southward certainly a coveted role across the entire animation manufacture, and David Trumble is a name to go along an center on in the story fine art space.

In this interview we cover a lot of ground (and it's a long 1 so strap in!)

We're going over his history with art, how he got into story art professionally, plus a lot of nitty-gritty details nearly the day-to-twenty-four hours life of a professional story artist working in the manufacture. Lots of gems in here if you want insider advice on the best traits to cultivate for work in this industry.

If story art is something you're interested in, whether as a fan or as a career, definitely cheque this ane out.

And if you're interested to acquire more than almost David's work you can check out his portfolio here.

How did you outset get into fine art? Did you have whatsoever formal training before getting into amusement fine art?

My parents tell me I've been drawing since I was two years old. So I literally can't remember a time I wasn't obsessed with storytelling.

But every bit with a lot of people in my industry, the path to animation was winding and unexpected. I have a twin brother who is as well a talented artist, and we spent most of our childhood making up stories together and cartoon a voluminous amount of pictures to go along with them. Our love of creating and acting out stories together was so intense that for a long menstruation we were oblivious to the world around us, in a creative bubble no-i knew how to burst.

He was my outset Story collaborator, kind of a hive mind situation (he is currently a standup comedian in the UK, but has worked equally a storyboard artist for commercials and other media). Past the fourth dimension we'd graduated high school both of our attentions had turned to movie-making and nosotros studied Film Production at the Arts University Bournemouth (AUB), one of the only practical courses in the United Kingdom, where we got to piece of work with 16mm film and both directed graduation shorts.

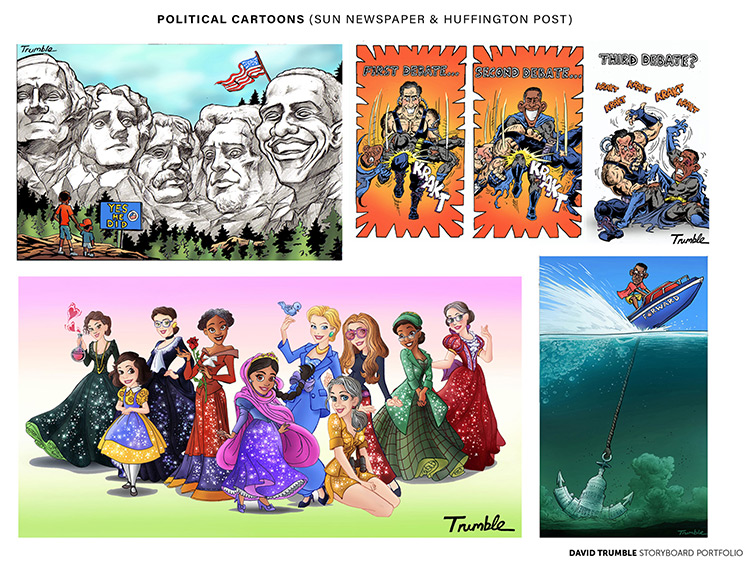

It was at that place that we constitute a larger group of collaborators, and continued to brand independent shorts well into our twenties. That, too, turned out to be a fleck of a bubble, and I ultimately became disenchanted with the rigors of low budget filming and barbarous back into freelance illustration, working as a political cartoonist for the Sun Newspaper and writing and illustrating children's books hither and there.

Information technology wasn't until the latter half of my twenties that I realized all the various career paths I had pursued all intersected in the realm of animation.

I had been generally aware of how storyboarding functioned, but it wasn't until I read Ed Catmull's book "Creativity, Inc." that I truly understood the collaborative, integral nature of the Story department and fell in love with it.

My whole life, I had kind of discounted animated features every bit a medium I adored but felt unqualified to pursue.

But it was in reading that volume that I realized that, after having tried my mitt at so many other storytelling mediums, I had been training for this skillset my whole life without fifty-fifty knowing it; every bit a draftsman, as a satirist, as a practical film-maker, all of these disciplines combined in Story.

So for the first time, I felt similar I had stumbled upon an creative pursuit to which I was uniquely suited. I simply came to it the long manner round.

How did you lot get your beginning gig doing story art & what did that look like?

There is truly no ane way to get into this business, and my story is a prime example.

In 2022 I applied for the Pixar Story internship and didn't get information technology. But in the course of not getting it I received what felt like a mixed message from the head of that internship, who had requested to encounter more of my work before sending a follow-up email to inform me they had filled all their spots.

I had a very supportive American girlfriend (with whom I was in a long altitude relationship from the United Kingdom) who strongly believed that this guy had wanted to requite me a shot.

My portfolio, while filled with analogy and cartooning examples, had been sorely lacking in terms of actual storyboards. So naturally I hadn't fabricated the cut, merely she urged me to continue pulling on this thread.

I had gone to the lengths of getting a visa to work in the U.S., on the off-chance that I got the internship. I basically took a leap of religion in both my life and my career by packing myself upwards in a suitcase and going straight to this Pixar veteran'due south Story masterclass in New York.

On the final twenty-four hours, terrified of being rejected in person just having been badgered by my ever-supportive girlfriend, I took the chance to evidence him my portfolio again at the shut of the two-day workshop.

To my absolute astonishment, he saw the start page of my portfolio pop up on my laptop and said "Oh…you're that guy!"

After hearing my story and chatting through everything I needed to improve upon, he told me he would brand it his mission to get me a job in animation.

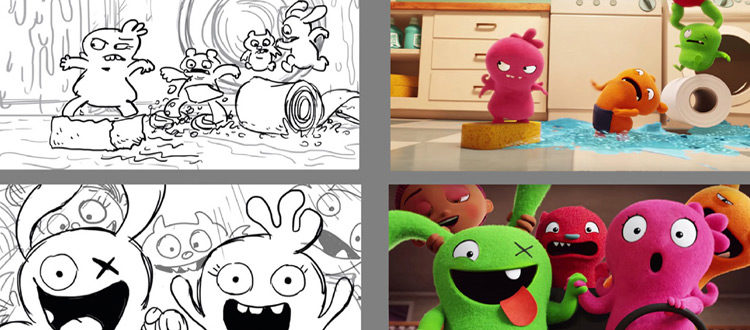

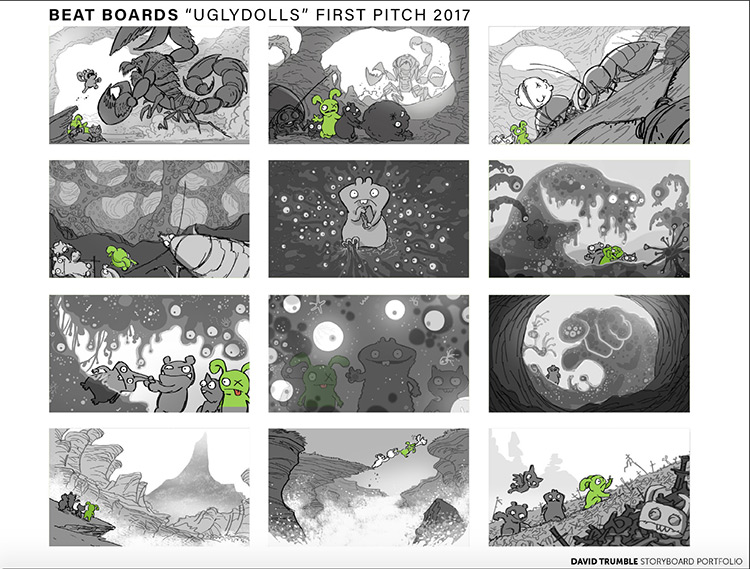

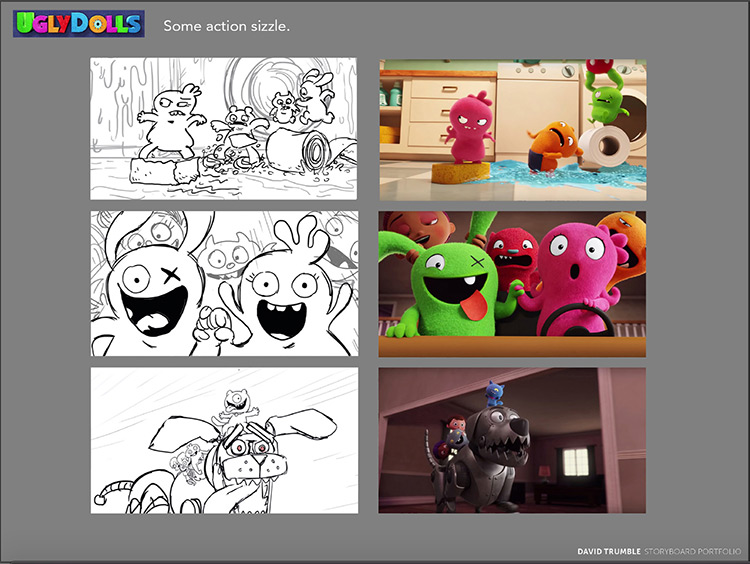

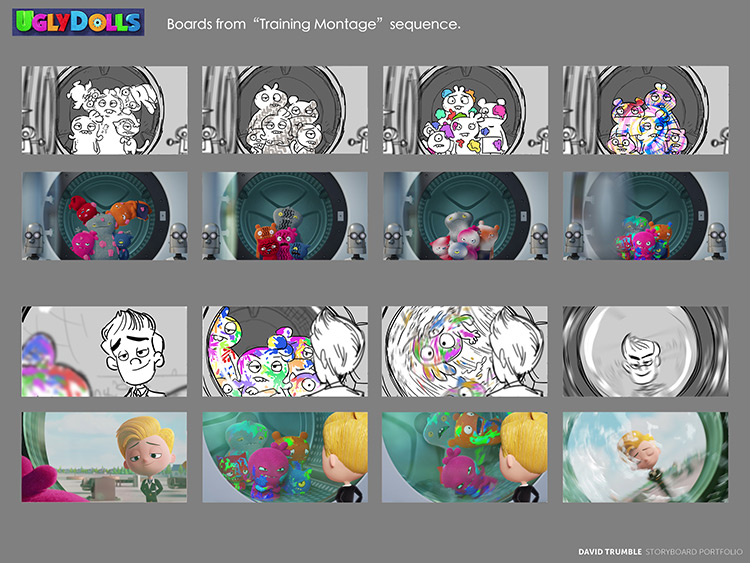

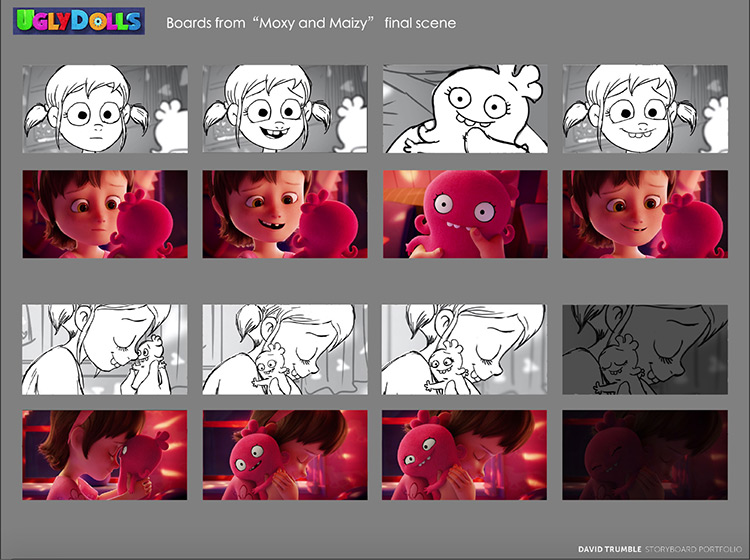

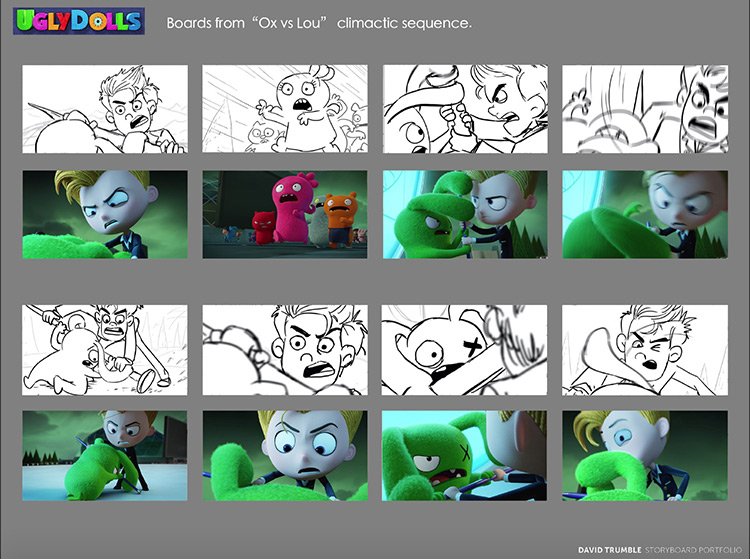

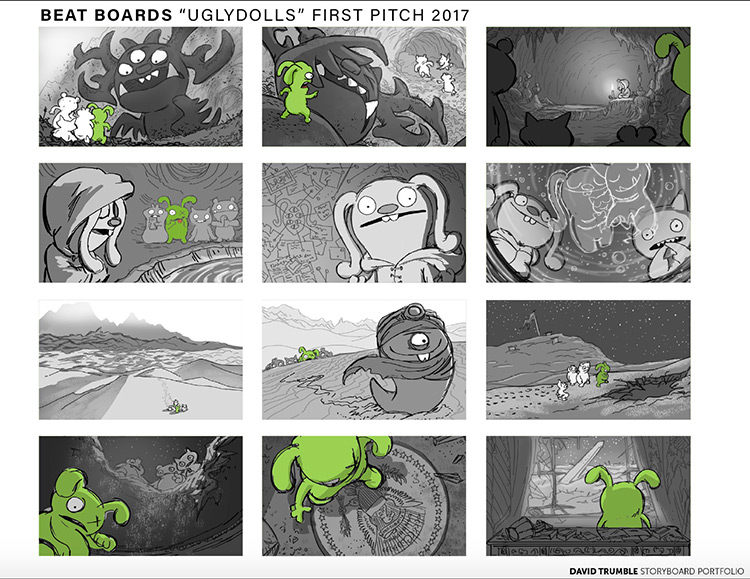

After ane year of sending him more of my work for feedback, taking online courses, and a few faux starts for potential jobs, he got me a job cartoon shell boards on my first animated feature, which would turn out to be "Uglydolls" by STX Entertainment.

I drew beat boards and visual evolution for multiple story pitches to the studio, then was hired on the film as a full-time Story Artist in 2016.

Though "Uglydolls" did not make a big splash in the marketplace, it introduced me to collaborators who continued to hire me on even more heady projects. I've boarded pre-viz sequences for Robert Rodriguez'south alive action superhero film "Nosotros Tin can Exist Heroes" for Netflix, have simply completed work on "Wendell & Wild" by cease-move fable Henry Selick in collaboration with director Jordan Peele, and this calendar month I'm nearly to begin work on Netflix Animation's "Charlie & The Chocolate Factory" series with Taika Waititi.

It'due south been a crazy-lucky run of projects. And they all happened because of referrals from a film that didn't do well, and that get-go pivotal foot in the door only happened because I failed to get into an internship.

And then yes, it's a funny, funny business. Because had I actually gotten what I was going for, I wouldn't exist where I am now.

But that bad luck was flipped on its head because I had people effectually me who believed in me and advocated on my behalf, my girlfriend, my mentor, and for that tireless support and inexplicable optimism I will always exist endlessly grateful.

For the storyboarding process, how do you approach drafting scenes from a script? Practice you get whatever directorial guidance, or are yous expected to but "understand" how to visualize it yourself?

Put information technology this mode, if you've been hired as a Story Artist on a feature and are being launched on a sequence, it means you've already demonstrated an understanding of cinematic techniques in your audience process.

There's a reason they call information technology "Story Artist" rather than just "Storyboard Artist".

They're hiring a storyteller, period.

So the amount of direction you receive in a launch depends very much on the managing director in question and their specific vision for the scene, but you are going into that process with a reasonable expectation of your fluency in visual language. Equally far every bit guidance is concerned, every director is different.

I've had directors who've drawn a series of quick thumbnails to map out how they see the shots progressing. And I've as well had directors who will be upfront almost genuinely non knowing how they want the scene to unfold.

Sometimes they'll encourage you to stick faithfully to the script, and sometimes they'll encourage you to disregard information technology entirely and try out new ideas. Many times, rather than receive a specific piece of management, I'll be given a reference point, a scene from a film or a moment of functioning that strikes a similar tone.

On my last feature "Wendell & Wild", managing director Henry Selick asked us all to watch Charles Laughton's 1955 film "Night of the Hunter" in order to get a sense of the composition and shot progression he was after.

Other times he would become outside of picture palace and refer to paintings, photography, way, annihilation that would requite united states of america a sense of the "experience" of what he was later on. Sometimes it comes downward to just a conversation about the themes or emotions the scene explores. Only in other instances, I've been launched by my Head of Story without the director present at all, and their first chance to actually directly me would be in response to my first pass of the boards. Which is pretty nervus-wracking to say the to the lowest degree.

This broad variety of approaches, while all having merit, can create a lot of anxiety in a Story Artist. Especially when yous're starting a project and take yet to fully slip into the groove with a director. And so information technology'southward important in the beginning few pitches to exercise great mindfulness and give yourself permission to "neglect" a bit.

Central to this is coming upwards with your own personal method that can be adapted to fit each consignment.

For me personally, I similar to spend the outset day thinking broadly, "globally", about the scene. And by that, I mean answering the unproblematic question of "What is this scene fundamentally almost?"

Obviously you have to go through the script and make annotation of all the elements that must exist juggled in terms of characters, actions and events, but pretty much any scene of a script can exist cleaved down to one essential beat that moves the story frontward. Something that can ideally be articulated in one judgement.

"This grapheme desire this", or "these characters discover this", or "this character loses this", etc.

And then I spend a lot of that first solar day just thinking about that. I sketch very fast thumbnails in my notebooks, collect reference materials, sentry similar scenes or sequences (helpful for activity), listen to motion picture soundtracks, and play/act the sequence over and over in my head while I'k doing other things like having a coffee or taking a walk, without putting pressure on myself to put it into boards immediately.

I get-go properly drawing on day two, usually the shots for which I've developed a clear vision regardless of where they sit in the scene chronologically, and so use them as my true due north equally I work out how the rest of it fits into the puzzle. Provided I have the fourth dimension, I try to permit 1 day in my schedule for freaking out, looking at what I've done and giving myself permission to completely rework it.

But as you fill in the gaps the sequence starts to tell y'all more and more the shape it's meant to exist so you ultimately end the procedure in service of, rather than dictating, the boards.

So if I've been doing it correct, I begin my assignment on a global level, and end it on a purely technical one, ticking off my shot-list and making sure the draftsmanship meets the standard for pitching.

The boilerplate turnaround for a draft of a sequence tends to be within a week, merely closer to the end of the schedule. It can be 2 or three days if not a one day turnaround, so it's helpful to accept an approach that is collapsible into different time-frames at a pinch.

Ultimately, your anchor will always be the blueprint of the script. So if you lose your manner but refer back to that.

And crucially, never put too much pressure on the first pass. My start passes tend to be mainly for me, my own cinematic sensibilities, then information technology gets pulled autonomously in the pitch and the second pass is about putting that preciousness abroad and bringing it closer to the director'south vision.

By the third pass, hopefully the scene has started to bear witness u.s.a. what works and what doesn't so it just becomes a matter of refinement.

Even if your boards stop up revealing fundamental flaws in this pattern, information technology'due south all good information for the director. The Story pipeline in animation is very much an iterative procedure of trial and error, so understand that even when things don't work, yous're actually making progress, ruling out wrong paths in society to hone in on the correct ane.

Know that going in, and create an approach to the boarding that works for you.

What does your typical twenty-four hours-to-24-hour interval look like in the animation pipeline?

This varies depending on whether y'all're remote or in-house, just unless the twenty-four hour period in question is a launch or a pitch solar day, you tend to be in accuse of your own time management.

The Caput of Story or a Production Banana may schedule check-ins midway through an assignment in case further brainstorming is required, and there'due south always the chance, peculiarly close to a screening, for a stream of additional shots and pickups to be requested alongside the sequence you're working on.

Nosotros ofttimes get requests from Editing, who are cutting scenes in tandem with Story, and if you're on a stop-motion you may go requests from the animation stage to clarify a shot or re-draw an environment and then that it aligns with the latest designs from Art or Props.

Conversely, Story/Edit Coordinators prove invaluable for reaching out on your behalf to other departments for the latest scripts, designs, and assets you might need for reference in your sequences. Story is the intersection point for a lot of departments, then having a proficient relationship with these teams is paramount.

Also because y'all're constantly reworking the motion-picture show through the various reels, you can go the odd moment where you lot depict either a prop or character that then ends up in the finished product pretty much as you had designed information technology, which tin can be a thrill to meet.

Merely for a few cursory exceptions, I've been a remote artist for every blithe feature I've worked on. And so when the pandemic hit information technology wasn't much of an adjustment for me at all.

That being said, there are pros and cons to being remote.

On the ane manus, your director and HODs trust y'all to schedule your workload so long every bit you deliver your work on time. You have flexibility, within reason, to give yourself breaks, practise, and generally balance your piece of work with your mental health.

Just on the other hand, y'all also don't get the same community feeling y'all'd become going into the studio every day, having lunch with peers, being inspired past unexpected conversations, etc.

That's why information technology's incumbent upon remote artists such equally myself to be proactive in creating and maintaining that collegiate temper from home.

I regularly text back and along with my fellow Story Artists to either kicking a few ideas around or offering moral support, and my last characteristic was the first I've boarded on that had a dedicated Slack channel for all departments.

I've been very fortunate to take experienced the best of both worlds, in that every production I've worked on has flown me to their respective studios in Burbank, Austin, and Portland for a week here and there when deadlines became burdensome.

That has immune me the chance to make stronger connections with my colleagues, across departments, relationships that have endured long after I've gone back to my function back home.

For all the boosted stressors of existence in the abdomen of the production beast, a few hairy days in the studio tin be an incredibly cathartic bonding experience for a crew. And you'll never forget someone who went through those wars with you lot.

So if you are a remote creative person and you become offered the chance to spend a few weeks in-firm I too highly recommend that.

What practice you personally think is the trickiest part of nailing a scene?

Every scene is tricky in its ain unique style. Which is why Story Artists demand such a broad purse of tricks to describe from.

But I'd say the trickiest part is figuring out which tricks not to bring to the table.

When you're essentially the first draft of a scene'south layout, information technology can exist very tempting to become overboard with the cinematic devices; throw in every cool camera move yous can think of, belabor every subtle tick of a functioning, or indulge in one-half a dozen inserts when a chief wide would accept washed the trick. Especially in computer blitheness where you can achieve any shot, inside reason.

The best storyboarding tip I ever received was from Valerie LaPointe of Pixar, a Story Artist on "Inside Out" and "Toy Story four" amongst others.

She said the simplest matter to me, which was:

"Board as though you're on a alive action movie set and the crew is running out of light."

This is because, though animation is seemingly limitless in what it can render, it is nevertheless congenital on rules developed by a medium defined by its practical limitations.

On a live action fix, for example, you can only utilize this actor for an afternoon. You lot can only interruption this prop once, or you only have the location for 1 mean solar day and there's a storm on the horizon.

Limitations, on the face of it, are negative things. Just they actually encourage (or rather, force) creativity and prioritizing of story mechanics over stylistic indulgence. And what's more than, the audience will thanks for it. Because they've been raised on the visual language created out of those limitations.

Throw in too many virtuoso shots and you risk losing the audience, considering they're too cine-literate, they subconsciously await judiciousness and clarity.

So the number i thing I've had to learn (the hard manner) in blitheness is imposing stricter limitations on myself, in guild to achieve more than with less.

Early in the storyboarding process for "Wendell & Wild", which is a stop-motion characteristic, I boarded an ambitious long accept that followed a character as it crawled under a larger fauna'due south legs. It was a existent "show-off" shot. Simply when I visited the product in Portland I realized that the geniuses in the workshop had had to build an entirely new rig with larger scale versions of the models simply to pull that shot off.

It concluded upwards in the movie and I'm very proud of it, but it really brought domicile to me only how much actress work I can create with a flick of my tablet pen, and how important it is to "earn" a shot like that if it requires the building of new avails.

So it's important to know when to reign yourself in.

As much as the film fanatic in me wants to create the most audacious, cinematic visuals possible, there are times when the simplest nigh understated techniques work the all-time.

That doesn't mean you can't go all out on a crazy camera move or play with an unconventional composition if it feels right. But you have to choose your moments.

The good news is the edit never lies. So if a scene you've delivered isn't landing, it doesn't matter how precious you feel most it. It goes in the bin.

Since a lot of story art tends to be more "cartoony", how oft do you do drawing from life? Do you feel realism is even so necessary equally a story artist?

I've washed my share of life cartoon in the past (it is a must for a Story portfolio) but I wouldn't say I've made information technology a big focus in my task. Probably because I don't subscribe to the notion that there's a huge difference between "realism" and "cartoony" in animation beyond the superficial.

When people say that an blitheness style is "cartoony" I think what they actually mean is "pushed".

So much of animation is near push/pull, in terms of lighting values, color temperatures, shape language, and character models.

Then at that place are certainly graphic symbol designs that are more stylized. Only even the animations that feature more than proportional trunk shapes are not what I would call "realistic". Their poses and movements are still "pushed" somewhere beyond reality, in order to be instantly recognizable to the viewer. And that's especially true in the Story process where we have to convey movement, behavior, and emotion in equally fast and clear a manner every bit possible.

Unlike animators who do incredible piece of work going granular into the subtle nuances of performance, Story Artists have to get their sequences through a ruthless serial of screenings. Then unless our characters and poses annals immediately, nosotros take to redraw.

To that cease, when I'grand boarding a sequence, it doesn't matter if the character has believable body dimensions or not. The underlying techniques we employ to convey their soul remains the aforementioned.

So to aspiring Story Artists, I would say: beingness good at cartoon bodies and poses from life is obviously an asset in this line of work, absolutely. But just exist aware that life drawings are static.

You tin draw a effigy hugging their legs next to a plate of fruit and information technology'll teach y'all a fair amount about how muscles sit down on a skeleton. But if yous want to know how to make that skeleton feel like it's live, take movement classes. Study theatrical acting, screen-take hold of dance and fight choreography, and sympathize how our body language is conveyed in flight.

Because that volition ultimately be what makes your characters feel vibrant in a story reel.

I noticed you've taken some classes with CGMA. How practice y'all feel about those courses in full general? And do you recall online courses tin can offer a replacement for more expensive higher classes?

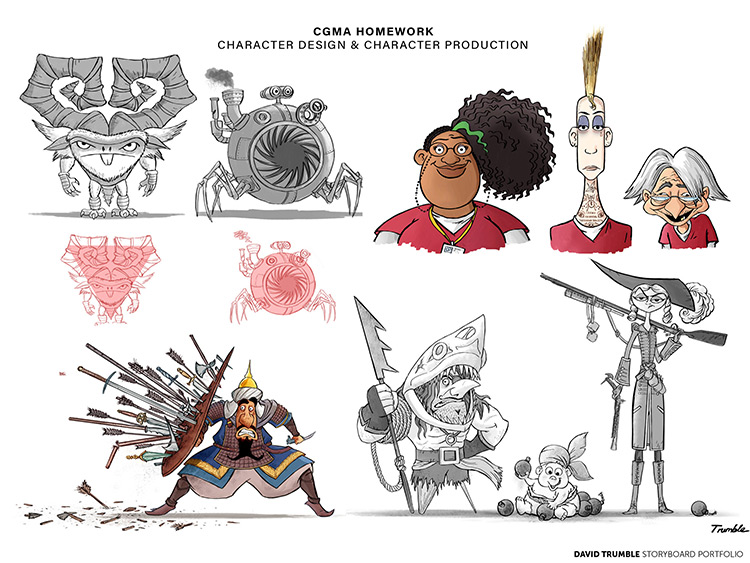

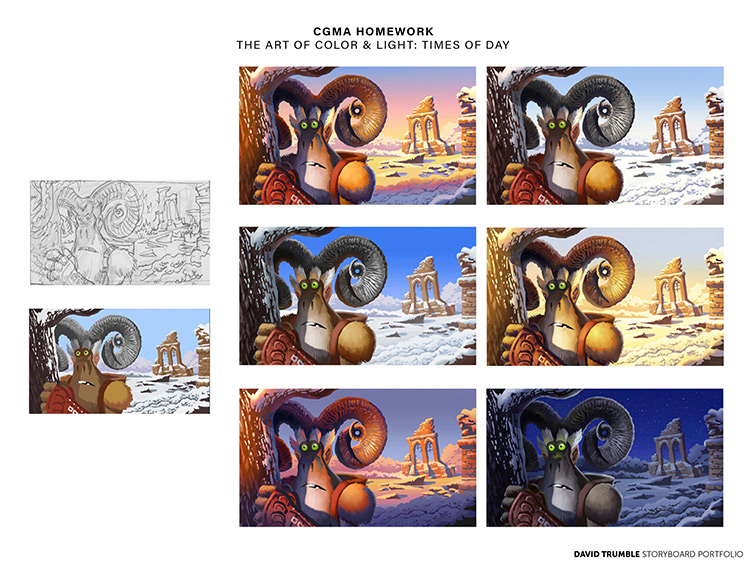

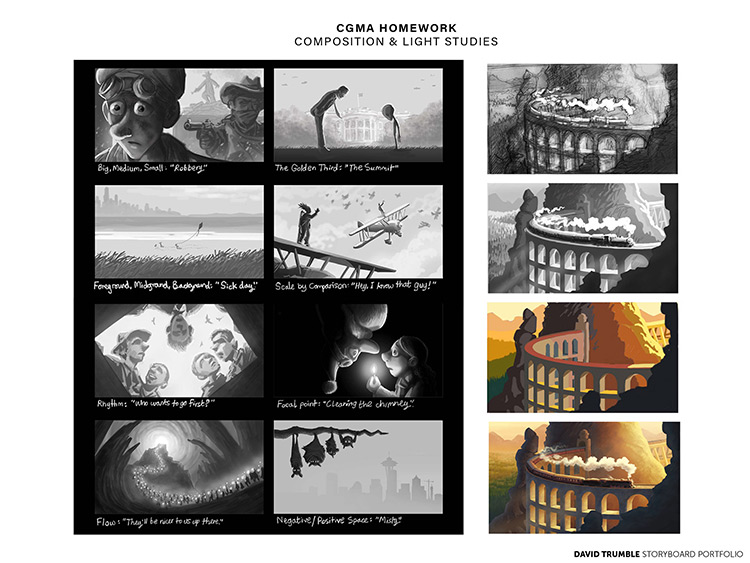

For CGMA I studied Storyboarding for Animation, The Art of Color and Light, Character Design, Character Production, and Anatomical Drawing at CGMA 2D Academy over a period of years as I was breaking in.

The Story grade, with a veteran Story Artist from DreamWorks and Illumination, made a huge deviation to the fashion I boarded. Because he hammered into me each week that I had to strip my illustrative style fashion, fashion dorsum.

That unmarried piece of advice fundamentally changed my whole approach. But I got a lot from all the courses.

The best part of a learning tool like CGMA is getting to interact with actual working professionals from the industry. And every ane of my tutors has stayed in touch and offered professional advice long later the courses were over, giving me tips on artist rates and even writing me recommendation letters for visa and green carte du jour applications.

Information technology's been an invaluable support to my journeying.

I certainly don't believe it'due south an either/or between online courses or expensive higher classes. I could not maybe replace the other, for the simple reason that neither are a guarantee of a job in animation.

It sounds maddening, but the truth is you could go to Cal Arts and not get the job you lot wanted at your chosen studio. And you could practise every course in CGMA's curriculum and not be what a recruitment officer was looking for on that particular twenty-four hour period.

Getting a chore in animation is 100% a moon-shot, dependent on so many variables. And nosotros're starting to see more and more how difficult it is for many groups to get their human foot in the door compared with others.

And then if you're a fellow member of a group that has less admission to these opportunities through no fault of your own, if you come from a country that has no major blitheness schools, if you don't have the coin or the ability to attend Cal Arts, or fifty-fifty if you landed on your career path later in life, so online courses like CGMA are wonderful resources to take available.

And I should stress that the Internet has fully democratized our ability to study our vocations beyond even paid courses similar CGMA.

Khan Academy, Pixar In A Box, Industry professionals running their own YouTube channels, and even just existence able to devour DVD/BluRay extras and commentaries in a matter of clicks, right downwardly to websites like Concept Art Empire itself.

In terms of education, aspiring animators have never had such a wealth of resources at their fingertips before. And that is surely a matter to celebrate.

Just exist aware that no certificate or tutorial contains the silver bullet that will land you a chore. That will be decided by what you lot accept from it, how well you apply information technology, and a gunkhole-load of luck.

If someone was putting together a portfolio to apply as a story artist, what should absolutely be in that portfolio? (or conversely, what should exist left out?)

This i's good and easy: Storyboards.

Lots of storyboards.

It's incredible how many portfolios are out there from talented people trying to get into Story jobs that don't have enough actual storyboards in them. Information technology's such a common fault, because most of usa come from a diversity of artistic backgrounds before getting into motion-picture show. And we feel the need to use it to bolster whatsoever deficits we might have starting out.

Merely no thing how great that other artwork is, a Story portfolio needs to be at least 70/30 (if not more than) Story-related piece of work.

Unless you're showcasing your ability to tell a story sequentially, cinematically and in terms of writing and conception, then you lot're wasting the employers' time.

The mentor who got me my starting time blithe characteristic job brash me for most a yr before my portfolio was up to scratch.

That meant culling about of the illustration and cartoonist work from my previous life, studying sequences from my favorite films, throwing out my first few boards and refreshing my portfolio with all-new sequences every few months.

With each pass I was losing more artwork and adding more Story.

In particular, I phased out my more than illustrative boards and replaced them with looser, scratchier panels more appropriate for the fast-paced sprint of production.

In the boards themselves, they don't desire to run into that you can draw (that will be apparent from your other pages). They want to know yous can communicate a story every bit speedily and direct as possible. If y'all don't have that, it doesn't matter how good your drawing is.

As for a general guideline, the strongest Story portfolios present the artist equally an "all-rounder", which means demonstrating 3 essential types of sequence: Drama, Comedy, and Activeness.

At that place'due south no reason yous tin't combine these three in one sequence. Simply for the do good of the reviewer try to create 3 different boarded sequences that emphasize each i.

Also devote at least two pages to supplementary "Gag" cartoons, to demonstrate your ability to take part in brainstorming "gag sessions" within a Story room, which is its own split skill.

Ultimately, someone reviewing your portfolio is looking for evidence of a firm grasp of movie-making. Proof that you lot sympathise photographic camera moves, values, and editing techniques, and that y'all can utilize this language to tell a story compellingly and sparingly.

Take a couple of your favorite scenes from animation or live action and break them downwardly into thumbnails, analyze them, put them back together, and then apply what you've learned to your own sequences.

Do speed-draws where you time yourself in order to develop a bailiwick for not over-drawing your boards, and un-learn any habits you developed in other mediums or roles. And practice this over and over and over. Because you won't get to the level you need correct away.

The magic sweet-spot that makes your portfolio exactly what the employer is looking for is something I can't say for sure, simply those are the elements your portfolio definitely can't do without.

One other common error: if you take artwork that's awesome just better applies to other departments within the field(such as grapheme design, concept art, backgrounds etc) include equally little as possible so it doesn't compete with your Story samples, or transport the recruiter a mixed message nearly the role y'all are fishing for.

Keep it focused.

You may feel more vulnerable dropping all your prettiest pictures and relying solely on your rough boards, but you are applying to work in Story. You're telling them y'all live, exhale, eat story.

And that means: boards, boards, and MORE BOARDS.

Where do you personally look for inspiration & ideas? Practice you have whatsoever favorite cartoons, comics, or anything that really impacted your style?

It may audio trite to say, but yous really have to expect for inspiration everywhere, both in art and in life.

Manifestly, I brand information technology a point to lookout films regularly to keep my cinematic skills honed (and they tend to fall far more than into the live action category than animation in my instance) but some of my all-time favorite Story contributions take been inspired past conversations or experiences with my loved ones.

I can blindside my head against the wall on a sequence all mean solar day, then take twenty minutes talking most life in general with a family member or my girlfriend and unlock the whole thing.

Having people around you with whom yous share groovy conversational chemistry is a major asset in this profession. You don't fifty-fifty take to hash out the specifics of a scene, only rather interrogate its themes or emotions on a homo level with someone you lot trust, and it tin brand all the difference.

Also, exist a religious hoarder of notions and ideas.

If you find something interesting, regardless of whether it applies to annihilation in your immediate workload, write information technology down, sketch information technology, screen grab information technology, record it, and save information technology for later.

Read books, listen to music, go to art galleries, accept lots of photographs, and if possible do it with someone who's equally passionate well-nigh them equally you are. It all helps to stir the pot creatively, and that's a process that'due south forever ongoing.

In regards to a more direct influence on the work in front of me, I am a strong believer in creating extensive libraries of visual references, inspiration, and enquiry for whatever project I am working on. If for no other reason than I really enjoy that initial discovery procedure.

Becoming familiar with a manager's mode, creating a playlist of other examples from the genre, and collating images that speak to the subject matter, all of these have proven helpful to me from task to job.

Pretty presently I'll brainstorm work on Taika Waititi's "Charlie & The Chocolate Factory" series at Netflix Blitheness. And I've had a wonderful fourth dimension just reading back through all of Roald Dahl'southward back-catalogue, looking dorsum on other Dahl adaptations, watching all of Taika'south movies and shows, and generally building up a foundational autograph for their mode, humor and sensibilities.

Now I should stress that all of this research could be thrown out the window in one case I accept a script and management in front end of me. So I never recollect of research as a rigid template. But yous never know when a tiny piece of information technology might come back around in a sequence or brainstorm.

This is what I meant earlier when I talked about thinking "globally" at the starting time of a project or assignment; it'southward like the analogy of having Scout mentality vs Soldier mentality.

Every bit a Story Artist, your job will eventually become intensely technical and logistical, charging through the schedule with very little bandwidth to do anything just focus on the task immediately alee of you.

You'll essentially go Gromit in "The Wrong Trousers" laying the pieces of track in front of the railroad train so the whole thing doesn't crash. So that's why I exercise everything I can at the beginning of the procedure to go equally broad and expansive an overview every bit I tin can before the train picks up speed.

That, and it'southward merely a lot of fun beingness a scholar of what you lot love.

For someone looking to go into storyboarding or whatsoever kind of amusement art, what departing advice would you have for them?

This i is very important to me, because I worked extremely hard to go to where I am today. But if I hadn't focused on this one thing it would accept all been for naught.

And that one thing is: Work on yourself.

Of all the advice I received from my tutors at CGMA, the affair that stayed with me the well-nigh was their insistence that in order to survive in this business, you have to exercise swell "in-the-room skills".

In other words, how to take harsh criticism, accept creative input, answer respectfully, and maintain a positive mental attitude to the work at all times.

This was echoed by the Head of Story for my first two animated features, who told me in our commencement ever meeting that "the one affair in this industry you lot can never become back is your reputation".

And he's so right.

Blitheness is a small, team-based customs where discussion travels fast. If you practise your job well and maintain good relationships, you'll go on to find piece of work. If you prove yourself to be hard to direct, unreceptive to candor, untrustworthy or disrespectful in whatever style, then your career will never go off the ground.

It may seem similar such an obvious thing, but before I got my first job I was absolutely not ready to be "in the room".

Like a lot of the young artists applying for jobs in the industry, I had cutting my teeth on other mediums: illustration, comics, cartooning, which are by their nature mostly solo endeavors.

I'd been my ain manager, my own editor, rarely collaborating with others. And the times I had collaborated revealed glaring deficits in my mental attitude and temperament that had to exist done away with before I entered the industry.

In that way, I'm incredibly relieved that information technology took me so long to get my first job. Because it provided me enough time to evolve into a truthful squad actor.

So yep, work on yourself. Not just for the wellness of your career, but the general health of your relationships overall.

Blitheness is an exceptionally stressful profession, and the Story department tin exist a highly pressurized environment, especially for a young artist. Because nosotros're constantly feeding the other departments all the way through the procedure Story tin, at times, feel like the middle of the production hurricane.

Deadlines can become overwhelming, directors and producers tin can hit creative walls, sequences tin can stop working, screenings can be demoralizing, merely the assembly line can never afford to suspension down.

As a effect, information technology is incumbent upon all of us to take great care to preserve our mental health and not become toxic or corking-ish in reaction to this environs, both for ourselves, and our young man collaborators.

And so my departing advice: getting this job requires organized religion/belief that borders on mirage, and that's okay. But yous must also empathise going in…you are going to exist part of a squad, and your ideas are not more important than those around y'all.

Y'all volition take to scout scenes you've poured your eye and soul into get torn apart, revised past another artist, or cut from the pic entirely. You will inevitably go from having all of the ability while yous're working on it to having none of the ability one time you've pitched it, and that'south okay . Information technology'south baked into the process, and you can't take whatsoever of it personally.

Your professional and emotional well-being depends upon information technology. At that place are so many resources out there detailing the technical arts and crafts of what's required to be a Story Artist. But a lot less material about how to live in information technology once you go in that location.

Safeguard your emotional well-being a little bit each day. Cultivate good relationships in and out of work, practice mindfulness and self-exam, meditate, exercise perspective and openness, and never lose sight of information technology.

Work on yourself.

Source: https://conceptartempire.com/david-trumble-interview/

0 Response to "Interview With Animation Story Artist David Trumble"

Postar um comentário